TL;DR: Here's how our scraper actually works—the architecture, and the problems we're still solving.

Why We're Sharing This

In our first post, we promised to build in public. That means sharing not just what we shipped, but how we built it. This is the story of our scraper: the system that calls phone numbers, listens to menus, and turns audio into structured data.

We're not sharing every implementation detail (we spent months on some of this), but we want to give you a real look at the architecture and the decisions that shaped it.

The High-Level Flow

Our scraper follows an exploration loop. Here's how it works:

Options?} end subgraph CALL["Phone Call"] C[Generate Button Sequence] --> D[Call via Twilio] D --> E[Press DTMF Tones] E --> F[Record Audio] end subgraph PROCESS["Audio Processing"] G[Transcribe via ElevenLabs] --> H[Parse with Gemini LLM] H --> I[Build Menu Node] end subgraph MERGE["Tree Update"] J[Merge into Existing Tree] --> K[Save Versioned JSON] end B -->|Yes| C B -->|No| L[Done - Full Tree Mapped] F --> G I --> J K --> B style INIT fill:#e1f5fe style CALL fill:#fff3e0 style PROCESS fill:#f3e5f5 style MERGE fill:#e8f5e9

Key constraints: - Only works for IVRs using DTMF tones (not AI voice bots) - Each call takes 60-90 seconds to capture the full menu - Some paths require 5-10 calls to fully explore

Simple in theory. In practice, every step has edge cases that took weeks to solve.

The Bug That Made Us Switch STT Providers

We started with Google Gemini for speech-to-text since Google was basically offering Gemini 2.5 pro and flash for free, and for a side project, "free" is compelling enough. The transcription quality was good, here's the final prompt which we used for transcription using Gemini 2.5 pro model.

You are an expert audio transcription service. Your task is to transcribe the provided audio with precise timestamps.

The final output must be a single JSON object conforming to this exact structure and format.

INSTRUCTIONS:

1. All timestamps ("start" and "end") MUST be in **total elapsed seconds** represented as a single **floating-point number**.

2. DO NOT use any other time format like "minutes:seconds". For e.g., "1:05.2" ie (One minute and 5.2 seconds) should be represented as 65.2 seconds and not like 105.2 seconds or "1:05.2" seconds in the start and end timestamps.

3. The transcription is for a legal document, so absolute accuracy is critical. Please do not omit any words, filler sounds (like "um," "uh"), or stutters.

...

SAMPLE JSON OUTPUT:

{

"transcript": "Thanks for calling. We are here to help. This call may be recorded for quality assurance.",

"chunks": [

{

"text": "Thanks for calling.",

"start_timestamp_seconds": 1.09,

"end_timestamp_seconds": 2.51,

"confidence": 0.9

},

..

],

"transcription_confidence": 0.95,

"total_call_duration": 66.0

}

Output Format:

- Return a single JSON object with the following exact fields:

...

- `start_timestamp_seconds`: Start time in seconds (float) with 0th second being the start of the audio.

- `end_timestamp_seconds`: End time in seconds (float) with 0th second being the start of the audio.

...

But there was a critical bug we only discovered after a month or so: timestamps were corrupted.

When audio hit the 1-minute mark, Gemini would return timestamps like this:

Audio at 1:05 (1 minute, 5 seconds) = 65 seconds

Gemini returned: 105 seconds ← Wrong!

It was reading "1:05" as "105" instead of converting to 65 seconds. Same for 2:01 → 201, and so on.

This broke everything. Our parser relies on timestamps to know where one menu ends and the next begins. With corrupted timestamps, we couldn't build accurate menu trees.

We tried patching it by detecting the pattern, applying corrections and using the previous timestamp as a fallback, but it was fragile. Every time something changed, we'd break again.

Eventually we switched to ElevenLabs. Their timestamps just work. As a bonus, transcription went from 30-60 seconds to 2-4 seconds per call. We should have switched sooner.

It's not all perfect with ElevenLabs, though. The response has issues detecting pauses in the audio accurately. Looks like STT is not their core focus, but we got free credits from a hackathon so we went with it. We detected any word chunk longer than 1 second as a pause and rewrote the transcript to add a pause between the chunks.

Lesson: We expected STT to be a solved problem by now. It's not. Voice is hard!

Parsing Menus with LLMs: A Sisyphean Task

Once we have a transcript, we need to extract structured data: What are the menu options? What buttons trigger them? Is this menu complete, or should we wait for more?

We use Gemini with a carefully crafted prompt that includes examples of different menu types. We tried few-shot prompting and it worked really well, but there were a lot of edge cases which needed us to continue iterating on the prompt. Even though we initially chose Gemini because it was free, it turned out to be a good call. Nowadays, Google seems to be rate limiting the free tier heavily so we are forced to use paid tier. We are still in Tier-1 and costs are not that high since we aren't scaling yet, more about that in a later post.

In practice, prompt engineering is a Sisyphean task. We've iterated on this prompt dozens of times. Every new phone tree reveals edge cases:

- Menus that say "press 1" vs "say billing"

- Options that loop back to the main menu

- Non-English language options

- Incomplete menus that get cut off

- "Stay on the line" options that aren't really options

- Menus that repeat when we keep listening.

- IVRs giving different "stay on the line" options the longer we let the call run.

We're still not satisfied with our prompt. It works for 90% of cases, but that last 10% keeps us up at night.

Lesson: LLM prompts are never "done." Budget for ongoing iteration.

A few things we are thinking about:

- Introducing a validation step to validate the parsed menus so we can make this a bit more reliable and "agentic" allowing it to handle new edge cases on its own without us having to iterate on the prompt.

- Exploring different models (OpenAI, Grok, etc.) to see if they can handle the edge cases better. This does require us to build a benchmarking system to compare the performance of different models.

The Data Model: Schema First

In our post-mortem blog post, we admitted that starting without a clear schema was a mistake. We've since fixed that.

Our menu tree uses five node types:

| Node Type | Example | What It Means |

|---|---|---|

| Select Menu Option | "Press 1 for billing, 2 for support" | Standard menu with choices |

| Provide User Input | "Enter your account number" | Requires user data |

| Reached Human | "Connecting you to an agent..." | Success - found a human |

| Wait | (silence or hold music) or the menu feels obviously incomplete | Menu incomplete, more coming |

| Terminate | (call dropped) or "Please hang up.." | Dead end, no further options |

Each menu is a tree. You can see this in the parsed menus which we display on the company pages.

We've seen phone trees 5+ levels deep. Getting this schema right took three refactoring cycles. Now it's stable, and merging new menus into existing trees actually works.

Lesson: Keep iterating :)

The Honest Reality: Costs and Constraints

A few things we're still working through:

Twilio is expensive. Making phone calls, recording audio, and storing recordings adds up fast. Twilio is currently our biggest cost. We're exploring alternatives.

Some IVRs don't cooperate. DTMF tones get ignored. Menus change based on time of day. Some systems hang up on automated calls. We mark these as "blocked" and move on.

Exploration is slow. Each call takes 60-90 seconds. With 5-10 menu paths per company, fully mapping one phone tree can take 25+ calls. We're optimizing, but there's a floor.

Scraping is not a solved problem. We're still working on this.

What This Means for Phone Supported

All of this engineering serves one goal: letting you skip the phone menu.

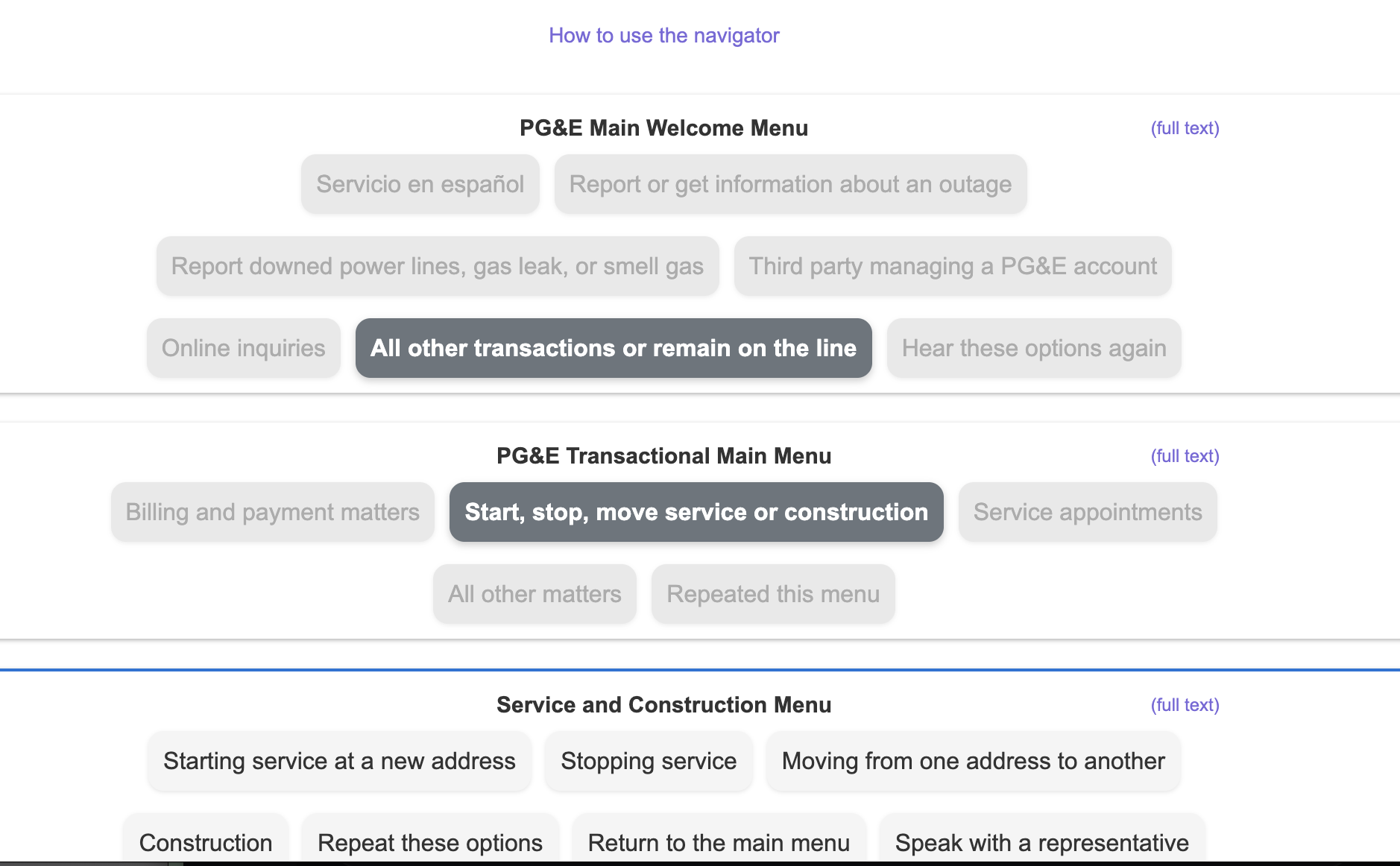

When you visit Phone Supported, you see a visual map of the phone tree. Click on "Billing," and we show you exactly what buttons to press—no more listening to "Press 1 for English" for the hundredth time.

An example of a scraped phone menu displayed on Phone Supported

An example of a scraped phone menu displayed on Phone Supported

The scraper runs in the background, keeping these maps fresh. When a company changes their IVR, we'll catch it and update the data.

What's Next

- We're scaling to 50+ companies and building automated re-scraping to detect menu changes.

- We want to expose more details about our scraping process, like how many calls were needed to fully explore a tree, how static the tree is, etc.

- Lastly, figure out a way to support parsing personalized menus like the ones where you can't proceed without having a valid account number or Social Security Number, etc and relationship with the company. We might have to crowdsource this part but we are not sure yet.

Follow our progress at @PhoneSupported